[Deep Learning] 2. Linear Algebra

Linear algebra

Linear algebra is essential for understanding and working with many machine learning algorithms, especially deep learning algorithms.

2.1 Scalars, Vectors, Matrices, and Tensors

- Scalars

- Just a single number, not like most of the other objects in linear algebra. We write scalars in italics and with lowercase variable names. e.g., “Let $s \in \mathbb{R}$ be the slope of the line,”

- Vectors

- An array of numbers. We can index the value with ordered numbers in it. We write vectors in bold and with lowercase names. e.g., \(\begin{equation} \mathbf{x} = \left[ \begin{matrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{matrix} \right] \end{equation}\) To access $x_1, x_3$ and $x_6$, we define the set $S={1,3,6}$ and write $\mathbf{x}_{S}$. ($-S$ means all the elements except for $1, 3$ and $6$)

- Matrices

- A 2-D array of numbers. We usually writhe matrices in bold with uppercase names. e.g., \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A = \left[ \begin{matrix} A_{1,1} & A_{1,2} \\ A_{2,1} & A_{2,2} \end{matrix} \right] \end{equation}\)

- Tensors

- An array with more than two axes. In general, an array of numbers that is arranged on a regular grid is known as a tensor. We denote a tensor with this typeface: $\mathtt{A}$. We identify the element of $\mathtt{A}$ at coordinated $(i,j,k)$ by writing $A_{i,j,k}$.

There are a few operations on these mathematical objects:

- Transpose: $(A^{\top}){i,j} = A{j,i}$. The mirror image of the matrix across the main diagonal, starting from the upper left corner. Vectors can be thought of as matrices that contain only one column, so the transpose of a vector is a matrix with only one row.

- Add: We can add matrices as long as they have the same shape: $\mathbf{C} = \mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}$ where $C_{i,j} = A_{i,j} + B_{i,j}$

- We can also add or multiply a scalar to a matrix: $\mathbf D = a\cdot \mathbf B + c$ where $D_{i,j} = a\cdot B_{i,j} + c$.

- Plus, there is implicit operation called broadcasting: $\mathbf C = \mathbf A + \mathbf b$ where $\mathbf b$ is a vector. the vector $\mathbf b$ is added to each row of the matrix.

2.2 Multiplying Matrices and Vectors

If $\mathbf A$ is of shape $m \times n$ and $\mathbf B$ is of shape $n \times p$, then $\mathbf C= \mathbf{AB}$ is of shape $m \times p$. The product operation is defined by \(\begin{equation} C_{i,j} = \sum_k A_{i,k} B_{k,j}. \end{equation}\) This is not a matrix containing the product of the individual elements. Such an operation is called the element-wise product, or Hadamard product, denoted as $\mathbf A \odot \mathbf B$.

The dot product between two vectors $\mathbf x$ and $\mathbf y$ of the same dimensionality is the matrix product $\mathbf{x^\top y}$.

Some useful properties of matrix product operations:

- Distributive: $\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{B+C}) = \mathbf{AB + AC}$.

- Associative: $\mathbf A (\mathbf{BC}) (\mathbf{AB}) \mathbf C$.

- Not commutative: $\mathbf{AB} = \mathbf {BA}$ does not always hold. (The dot product between two vectors is commutative.)

- Transpose of a product: $(\mathbf{AB})^\top = \mathbf B^\top \mathbf A^\top$. (Commutative dot product can hold by this property.)

A system of linear equations is written by: \(\begin{equation} \mathbf{Ax}=\mathbf{b} \end{equation}\) where $\mathbf A \in \mathbb R^{m \times n}$ is a known matrix, $\mathbf b \in \mathbb R^m$ is a known vector, and $\mathbf x \in \mathbb R^n$ is a vector of unknown variables we would like to solve for. We can rewrite equation (4) as \(\begin{align} \mathbf{A}_{1,:}\mathbf x &= b_1 \\ \mathbf{A}_{2,:}\mathbf x &= b_2 \\ &\cdots \\ \mathbf{A}_{m,:}\mathbf x &= b_m \end{align}\) or even more explicitly, we can rewrite $\mathbf x$ with all elements of it.

2.3 Identity and Inverse matrices

There is a powerful tool called matrix inversion that enables us to solve linear system as the above.

Before of that, we first need to define the concept of and identity matrix, a matrix that does not change any values when it is multiplied to a vector(or matrix). We denote the identity matrix with $n$-dimensional vectors as $\mathbf I_n \in \mathbb R^{n\times n}$, and \(\begin{equation} \forall \mathbf x \in \mathbb R^n , \mathbf I_n \mathbf x = \mathbf x. \end{equation}\) An identity matrix has all zero values except for diagonal values with one.

Then, we also can denote the matrix inverse of $\mathbf A$ as $\mathbf A^{-1}$ and define as \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A^{-1} \mathbf A = \mathbf I_n \end{equation}\) We can now solve equation (4) using the following steps: \(\begin{align} \mathbf{Ax} &= \mathbf b \\ \mathbf A^{-1} \mathbf{Ax} &= \mathbf A^{-1} \mathbf b \\ \mathbf I_n \mathbf x &= \mathbf A^{-1} \mathbf b \\ \mathbf x &= \mathbf A^{-1} \mathbf b \end{align}\) So, we must find $\mathbf A^{-1}$ to solve the system. However, the existence of it depends on $\mathbf A$.

When $\mathbf A^{-1}$ exists, we can find it with several different algorithms.

2.4 Linear Dependence and Span

In equation (4), It is possible for the system of equations to have no, infinitely many or exactly one solution. For $\mathbf A^{-1}$ to exist, the system must have exactly one solution for every value of $\mathbf b$. However, it is not possible to have more than one but less than the infinite for a particular $\mathbf b$ because if both $\mathbf x$ and $\mathbf y$ are solutions, then \(\begin{equation} \mathbf z = \alpha \mathbf x + (1-\alpha) \mathbf y \end{equation}\) is also a solution for any real $\alpha$.

To find out how many solutions the equation has, think of each column of $\mathbf A$ as a vector from the origin.

The span of a set of vectors is the set of all points obtainable by linear combination of the original vectors. Determining whether $\mathbf{Ax} = \mathbf b$ has a solution thus amounts to testing whether $\mathbf b$ is in the span of the columns of $\mathbf A$. This particular span is known as the column space, or the range, of $\mathbf A$.

Given $\mathbf b \in \mathbb R^m$, the column space of $\mathbf A$ must be all of $\mathbb R^m$ to have a solution. If any point in $\mathbb R^m$ is excluded from the column space, that point is a potential value of $\mathbf b$ that has no solution.

The column space of $\mathbf A$ be all of $\mathbb R^m$ implies immediately that $\mathbf A$ must have at least $m$ columns, that is, $n \ge m$.

For example, consider a 3 x 2 matrix. The target $\mathbf b$ is 3-D, which means $\mathbf x$ is only 2-D vector, then modifying the value of $\mathbf x$ at best enables us to trace out a 2-D plane within $\mathbb R^3$. The equation has a solution if and only if $\mathbf b$ lies on that plane.

(Caution: This is only a necessary condition, consider \(\left[ \begin{matrix} 2 & 2 \\ 1 & 1 \end{matrix} \right]\), it fails to encompass all of $\mathbb R^2$ even though there are two columns.)

Formally, this redundancy is called as linear dependence. A set of vectors is linearly independent if “no vector in the set is a linear combination of the other vectors”.

Back to the inverse, we know that the equation should have at most one solution for each $\mathbf b$. It means that $n=m$ because if the number of columns is larger than of rows, there is more than one way of parameterizing each solution.

Together, it means that for existing the inverse, the matrix must be square that all the columns be linearly independent.

(A square matrix with linearly dependent columns is known as singular.)

It is also possible to find a solution if $\mathbf A$ is not square or square but singular, but we cannot use the method of matrix inversion to find it.

2.5 Norms

- Norms

- The function to measure the size of vectors. Formally, the $L^p$ norm is given by \(\begin{equation} \lVert \mathbf x \rVert_p = \left(\sum_i \lvert x_i\rvert^p\right)^{1\over p} \end{equation}\) for $p \in \mathbb R, p \ge 1$.

Norms are functions mapping to non-negative values. And a norm satisfies the following properties:

- $f(\mathbf x) = 0 \Rightarrow \mathbf x = 0$

- $f(\mathbf{x+y}) \le f(\mathbf x) + f(\mathbf y)$ (the triangle inequality)

- $\forall \alpha \in \mathbb{R}, f(\alpha \mathbf{x}) = \lvert \alpha \rvert f(\mathbf{x})$

$L^2$ norm is known as the Euclidean norm and it is also common to measure the size of a vector using the squared $L^2$ norm, which is simply $\mathbf x^\top \mathbf x$.

However, in many contexts, the squared $L^2$ norm may be undesirable because it increases very slowly near the origin. In these cases, the $L^1$ norm can be used to discriminate between elements that are exactly zero and elements near zero.

There is no $L^0$ norm but one other norm that commonly arises in ML is the $L^\infty$ norm, also known as the max norm. \(\begin{equation} \lVert \mathbf x \rVert_\infty = \max_i \lvert x_i \rvert \end{equation}\)

Also, there is a way to measure the size of matrix. The most common way is Frobenius norm: \(\begin{equation} \lVert \mathbf A \rVert_F = \sqrt{\sum_{i,j} A^2_{i,j}} \end{equation}\) which is analogous to the $L^2$ norm of a vector.

2.6 Special Kinds of Matrices and Vectors

- Diagonal matrix

- A matrix which consists mostly of zeros and have nonzero only along the main diagonal: $D_{i,j}=0$ for all $i \ne j$.

- Symmetric matrix

- A matrix which equals to its own transpose: \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A = \mathbf A^\top. \end{equation}\)

- Unit vector

- A vector with unit norm: \(\begin{equation} \lVert \mathbf x \rVert_2 = 1. \end{equation}\)

A vector $\mathbf x$ and $\mathbf y$ are orthogonal to each other if $\mathbf x^\top \mathbf y=0$. This means that they are at a 90 degree angle to each other. (+ If the vectors are also have unit norm, we call them orthonormal)

- Orthogonal matrix

- A square matrix whose rows are mutually orthonormal and also columns are mutually orthonormal: \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A^\top \mathbf A = \mathbf A \mathbf A^\top = \mathbf I \end{equation}\) Which implies that \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A^{-1} = \mathbf A^\top \end{equation}\)

2.7 Eigendecomposition

We can decompose matrices to discover the true nature, which shows us information about their functional properties that is not obvious from the representation of the matrix as an array of elements.

One of the kinds of matrix decomposition is eigendecomposition. (which is most widely used)

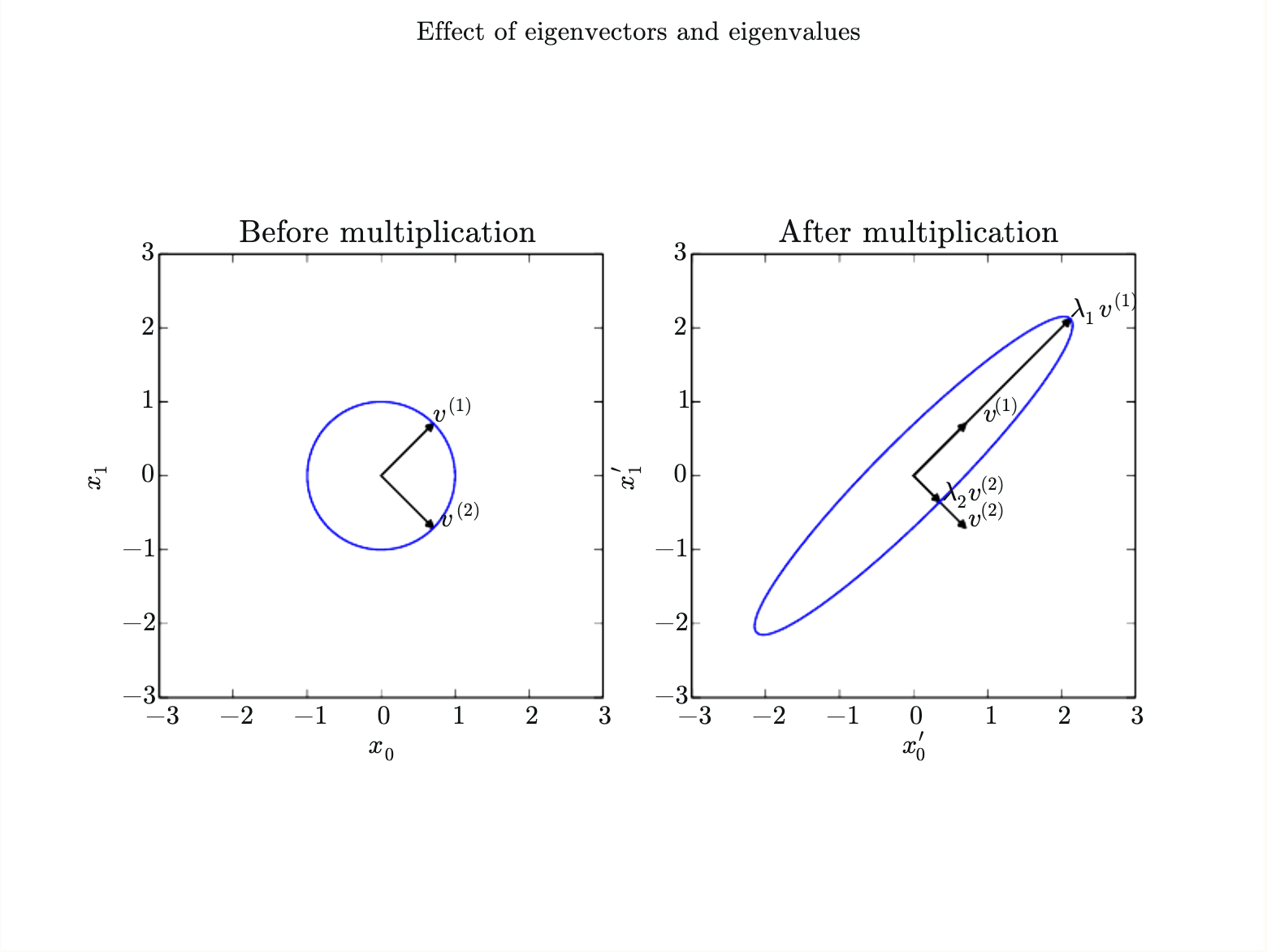

We can denote an eigenvector of a square matrix $\mathbf A$ as a nonzero vector $\mathbf v$and define as follows: \(\begin{equation} \mathbf {Av} = \lambda \mathbf v \end{equation}\) The scalar $\lambda$ is the eigenvalue corresponding to $\mathbf v$

Suppose that $\mathbf A$ has $n$ linearly independent eigenvectors with corresponding eigenvalues, We may from a matrix $\mathbf V = [\mathbf v^{(1)}, \dots, \mathbf v^{(n)}]$ and a vector $\mathbf \lambda = [\lambda_1, \dots, \lambda_n]^\top$. Then, the eigendecomposition is given by \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A = \mathbf V \text{diag}(\mathbf \lambda) \mathbf V^{-1} \end{equation}\)

Figure 2.3: An example of the effect of eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

Figure 2.3: An example of the effect of eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

$\mathbf A$ as scaling space by its eigenvalues in direction of its corresponding eigenvectors.

If $\mathbf A$ is real symmetric matrix, it can be decomposed into \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A = \mathbf{Q \Lambda Q^\top} \end{equation}\) where $\mathbf Q$ is an orthogonal matrix composed of eigenvectors, and $\mathbf \Lambda$ is a diagonal matrix.

The eigendecomposition may not be unique ,but conventionally sort the entries of $\mathbf \Lambda$ in descending order. Under this convention, the eigendecomposition is unique only if all the eigenvalues are unique.

The eigendecomposition tells us many useful facts

- The matrix is singular if and only if any of the eigenvalues are zero.

- The eigendecomposition of a real symmetric matrix can also be used to optimize quadratic expressions of the form $f(\mathbf x) = \mathbf{x ^\top A x}$ subject to $\lVert \mathbf x \rVert_2 = 1$.

- Whenever $\mathbf x$ is an eigenvector of $\mathbf A$, $f$ is the corresponding eigenvalue.

- A matrix whose eigenvalues are

- all positive is called positive definite.

- They guarantee that $\mathbf{x^\top Ax}=0 \Rightarrow \mathbf x = 0$.

- all positive or zero valued is called positive semidefinite.

- They guarantee that $\forall \mathbf x, \mathbf{x^\top Ax} \ge 0$.

- all negative is called negative definite.

- all negative or zero valued is called negative semidefinite.

- all positive is called positive definite.

2.8 Singular Value Decomposition

SVD provides another way to factorize a matrix, into singular vectors and ** singular values**. The SVD enables us to discover some of the same things as the eigendecomposition does.

The SVD is a kind of general version of eigendecomposition, which is only applicable to a square matrix, because every real matrix has a singular value decomposition.

In section 2.7, we can rewrite a square matrix $\mathbf A$ as \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A = \mathbf V \text{diag}(\mathbf \lambda) \mathbf V^{-1}, \end{equation}\) and SVD can rewrite any real matrix $\mathbf A$ in a similar form \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A = \mathbf {U D V^\top} \end{equation}\)

- $\mathbf U$: the columns of $\mathbf U$ are know as the left-singular vectors of $\mathbf A$, which are the eigenvectors of $\mathbf{AA^\top}$.

- $\mathbf V$: the columns of $\mathbf V$ are know as the right-singular vectors of $\mathbf A$, which are the eigenvectors of $\mathbf{A^\top A}$.

- $\mathbf D$: the diagonal of $\mathbf D$ are known as the singular values of $\mathbf A$.

2.9 The Moore-Penrose Pseudoinverse

Alike the SVD, matrix inversion is not defined for matrices that are not square.

For a non-square matrix $\mathbf A$, we want to obtain left-inverse $\mathbf B$ that satisfies \(\begin{align} \mathbf{Ax=y} \\ \mathbf{x=By} \end{align}\) We may or may not find the mapping from $\mathbf A$ to $\mathbf B$ using the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse , which of $\mathbf A$ is defined as a matrix \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A^+ = \lim_{\alpha\rightarrow 0} (\mathbf{A^\top A} + \alpha \mathbf I)^{-1} \mathbf A^\top. \end{equation}\) However, practical algorithms are based not on this definition but the SVD. \(\begin{equation} \mathbf A^+ = \mathbf{VD^+U^\top}, \end{equation}\) where $\mathbf D^+$ is obtained by taking the reciprocal(역수) of its nonzero elements then taking the transpose of it.

- Exactly one solution: this is the same as the inverse.

- When $\mathbf A$ has more columns than rows, then solving a linear equation using $\mathbf{x = A^+ y}$ provides one of the many possible solutions.

- In this case, this gives us the solution with the smallest norm of $\mathbf x$

- While when $\mathbf A$ has more rows than columns, it is possible to be no solution.

- In this case, this gives us the solution with the smallest error $\lVert \mathbf{Ax - y} \rVert_2$.

2.10 The Trace Operator

- Trace

- The sum of all the diagonal entries of a matrix \(\begin{equation} \text{Tr}(\mathbf A) = \sum_i \mathbf A_{i,i}. \end{equation}\)

It is useful for removing summation in operation. For example, an alternative way of writing Frobenius norm of a matrix: \(\begin{equation} \lVert \mathbf A \rVert_F = \sqrt{\text{Tr}(\mathbf{AA^\top})} \end{equation}\)

Some properties:

- $\text{Tr}(\mathbf A) = \text{Tr}(\mathbf A^\top)$

- $\text{Tr}(\mathbf{ABC}) = \text{Tr}(\mathbf{CAB}) = \text{Tr}(\mathbf{BCA})$

- if the shapes of the corresponding matrices allow the resulting product to be defined.

2.11 The Determinant

- Determinant

- The determinant of a square matrix is a function that maps matrices to real scalars. \(\begin{equation} \text{det}(\mathbf A) \end{equation}\)

- The product of all the eigenvalues of the matrix

- The absolute value as a measure of how much multiplication by the matrix expands or contracts space.

- If the determinant is 0, then space is contracted completely along at least one dimension, causing it to lose all its volume.

- If the determinant is 1, then the transformation preserves volume.

Extra

- Gradient

- Given a multivariate function $f: \mathbb R^n \rightarrow \mathbb R$, \(\begin{equation} \nabla f= \left[{\partial f(x_1,\dots ,x_n) \over \partial x_1}, \dots, {\partial f(x_1,\dots ,x_n) \over \partial x_n} \right] \end{equation}\)

- Jacobian

- Given a multivariate function $f: \mathbb R^n \rightarrow \mathbb R^m$, \(\begin{equation} J = \left ( \begin{matrix} {\partial f_1 \over \partial x_1} & \cdots & {\partial f_1 \over \partial x_n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {\partial f_m \over \partial x_1} & \cdots & {\partial f_m \over \partial x_n} \end{matrix} \right) \end{equation}\)

- Hessian

- Given a multivariate function $f: \mathbb R^n \rightarrow \mathbb R$, \(\begin{equation} H = \left ( \begin{matrix} {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_1^2} & {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_1 \partial x_2} & \cdots & {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_1 \partial x_n} \\ {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_2 \partial x_1} & {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_2^2} & \cdots & {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_2 \partial x_n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_n \partial x_1} & {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_n \partial x_2} & \cdots & {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_n^2} \end{matrix} \right) \end{equation}\)

- Laplacian

- Given a multivariate function $f: \mathbb R^n \rightarrow \mathbb R$, \(\begin{equation} \nabla^2 f = trace(H) = {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_1^2} + {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_2^2} + \cdots + {\partial^2 f \over \partial x_n^2} \end{equation}\) This is extremely important in mechanics, electromagnetics, wave theory, quantum mechanics, and image processing (e.g., Laplacian of Gaussian function)

- Moment

- A quantitative measure of the shapes of a function \(\begin{equation} \mu_n = \int^\infty_{-\infty} (x-c)^n f(x) dx \end{equation}\) This is $n_{th}$ moment and $c$ is usually zero.

- 1st raw moment: mean

- 2nd central moment: variance

- with $c$ being the mean.

- when $f(x)$ is a multivariate function, the 2nd moment is a covariance matrix.

- Variance

- A measure of the spread of the data in a data set with mean. \(\begin{equation} \sigma ^2 = {\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar X)^2 \over (n-1)} \end{equation}\)

- Covariance

- A measure of how much each of the dimensions varies from the mean with respect to each other. \(\begin{equation} \text{cov}(X, Y) = {\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar X)(Y_i - \bar Y) \over (n-1)} \end{equation}\) The negative output is possible.

- Covariance Matrix

- Representing covariance among dimensions as a matrix.

2.12 Principal Components Analysis

PCA is a useful mathematical tool from applied linear algebra. It is a simple, non-parametric method to reduce a complex data set to a lower dimension. (compression)

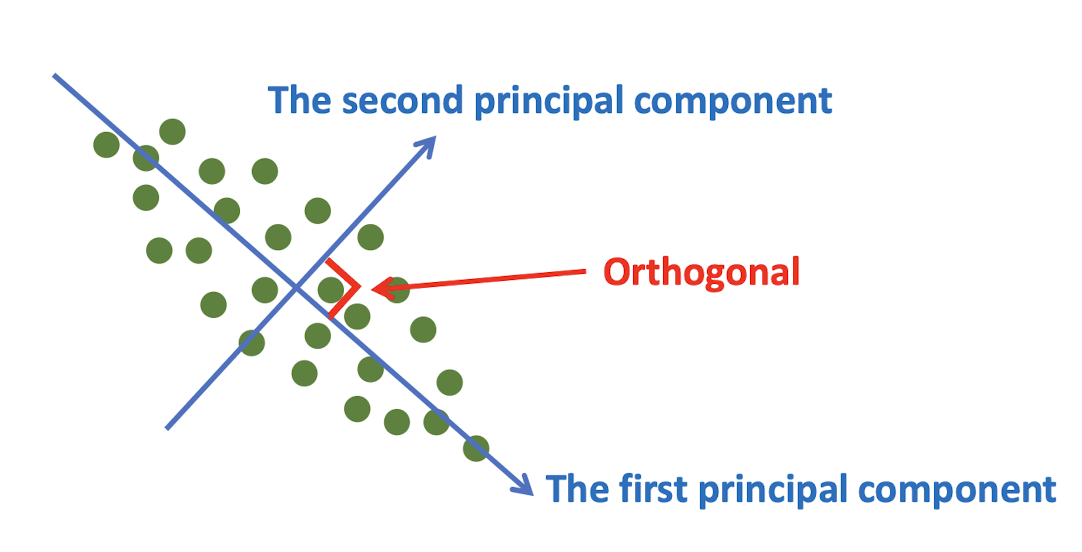

Characteristics

- Identifying directions to have high variances

- The first principal component has the most variance.

- Each succeeding component in turn has the highest variance possible under the constraint that it be orthogonal to the preceding components.

Concept • An orthogonal transformation • Conversion of correlated observations into uncorrelated variables • Dimensionality reduction • Minimize the loss of information = maximize the variance of data • Provides an optimal solution if the samples are from Gaussian distribution

Computation of PCA • Analyze the data covariance matrix • Using eigenvalue decomposition or singular value decomposition

PCA can be computed with the procedure below Given a dataset $x_i \in \mathfrak R^m (i=1, \dots, n)$, covariance $S_x = {1\over n} \sum^n_{i=1} (x_i \bar x)(x_i-\bar x)^\top$

Then, $S_y = {1\over n} \sum^n_{i=1} (y_i \bar y)(y_i-\bar y)^\top = W^\top S_x W$, where $y_i = W^\top (x_i - \bar x)$.

With the objective: $W^*=\underset W {\arg\max} \lvert W^\top S_x W \rvert$, We can reduce the equation with eigendecomposition or SVD. \(\begin{equation} V =\left[ I_{m\times k} \vert 0_{m\times(m-k)} \right] \Leftrightarrow W=U_{1:k} \end{equation}\)

Summary :

- Organize data as an $m \times n$ matrix, where $m$ is the number of measurement types and $n$ is the number of samples.

- Subtract off the mean for each measurement type.

- Calculate the SVD or the eigenvectors of the covariance.